Towards ecologically intensive agriculture in Africa

17 February 2020According to UNDP figures, 31 out of 36 countries with a low HDI (Human Development Index) are in sub-Saharan Africa. The region is home to more than half the world's.

- 0

- 1 views

According to UNDP figures, 31 out of 36 countries with a low HDI (Human Development Index) are in sub-Saharan Africa. The region is home to more than half the world's.

Forecasts on the potential of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa on the basis of which large scale land transactions are being deployed, are based on a rhetoric of the "empty continent", adapted to establish agricultural policies as well as to justify all manner of greed. This thesis of the existence of "dormant resources" which would amount to approximately a billion hectares in useful agricultural surfaces area is incorrect. This article introduces the concept of actual availability of agricultural land and takes into account all the real estate constraints in order to assess the surface area likely to be actually devoted to agriculture.

The most optimistic production forecast theories rely on the rhetoric of an Africa rich in “dormant land resources", "vacant and without masters". There would be an abundance of available land, unassigned and ready to be used. 50 million hectares of arable land has already changed hands, between 2000 and 2018, 90% of which to the benefit of foreign interests (Oakland Institute, 2019). It is thought to be concentrated in certain regions particularly favoured in terms of land fertility, access to water and transport infrastructure.

This rhetoric is also well adapted to respond to the question of the Africa’s ability to occupy an agricultural labour force which is very likely to increase by approximately 330 million people over the 40 years between 2010 and 2050 and its ability to cover its own food needs by farming its available land.

The reality is more complex. Land availability is a relative concept in a continent where various modes of ownership and use overlap, but which is also marked by strong agronomic and ecological constraints.

A robust, detailed knowledge of agricultural availability is essential to estimate production potential as well as installation possibilities for newcomers. On the basis of new estimates and a more demanding analysis, this case study draws from a previous Willagri article (20 November 2017), entitled “The Myth of the abundance of arable land in Africa", and attempts to answer three questions: Can we assess the true availability of agricultural land? Can we identify the constraints that are opposed to its extension? And glimpse the dynamics in play when it comes to commercialising African land?

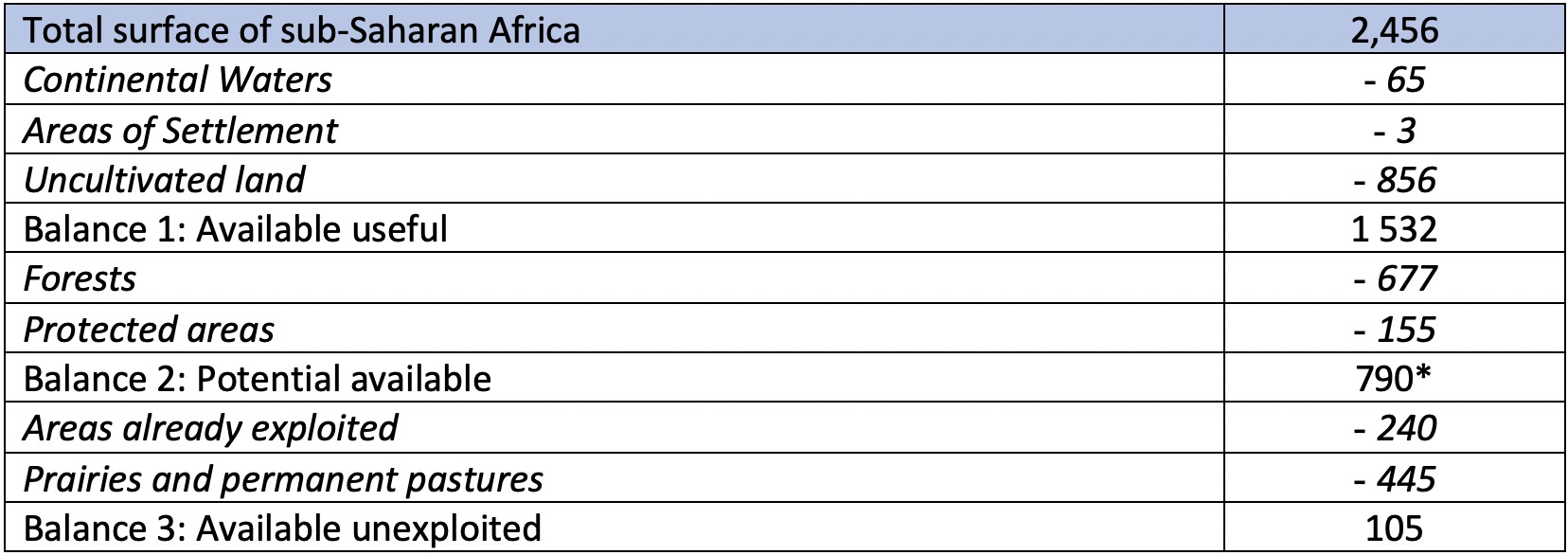

In order to assess the surfaces likely to be devoted to agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa, let’s introduce the notion of land availability by distinguishing 5 balances one after another:

Let us measure this using data from the recent Bauhaus Luftfahrt carried out in Munich (Riegel, Roth and Batteiger, 2019) established on the basis of high resolution geospatial data to estimate the areas devolved to different types of use of the soil, supplemented by that of the United Nations for agriculture and power supplies (FAOSTAT).

The approach is called "residual", in that we gradually identify the areas which are not available for agriculture, thus varying the balance if changes occur in any of the subject areas.

With a total of 2 456 million hectares, the sub-Saharan sub-continent is vast.

The areas considered to be useful, i.e. virtually likely to be devoted to an economic activity of one kind or another, cover nearly 1 537 million ha of this zone, after deduction of continental waters, land considered non-cultivatable because it is affected by desertification and areas of population settlement, cities, transportation routes, etc. (ELD-UNEP, 2015; Riegel et al., Op. cit.).

To obtain the potential, we must remove the forests (677 Mha) and protected areas (155 Mha[1]), recognized for their ecological value and whose exploitation for agricultural purposes seriously affect environmental balance.

Within the potential available balance, the land already exploited, with annual and long-term cultivation account for approximately 240 million hectares (OECD/FAO, 2016; FAOSTAT, 2019).

Finally, prairies (including the trails, pastures and cropland, comprising trees, pasture and fodder) devoted to permanent pasture and extensive pastoralism, cover approximately 29% of the useful available surface areas (not uncultivated for livestock), or 445 million ha (FAOSTAT, 2017).

*A correction is made in order to take account of the overlap between protected areas and forests, estimated at 12% (Riegel and Al, 2019). The sources of data are indicated at the end of the article.

©GRET

The net balance of exploitable land is approximately 100 million hectares. The accuracy of the data is relative, but one conclusion appears evident: "There is still substantially less available viable land than is often stated once taken into account all the constraints and trade-offs between various functions" (Lambin et al. , 2014, p. 900). We must include functions other than those which are strictly agronomic or economic and often obscured in arguments which boast the opportunities associated with the agricultural potential of the sub-Saharan sub-continent.

The economic boom in West Africa is related to the agriculture and agri-food sectors. Feeding 500 million increasingly urbanised Africans by 2030 has kickstarted the growth of the agriculture and.

This dossier consists of two distinct parts:

1) An overview of protective measures against the importation of agricultural products: current situation and key issues for sub-Saharan Africa by Jean-Christophe Debar and Abdoul Fattah Tapsoba from the FARM Foundation;

2) A debate between Jean-Christophe Debar (President of FARM), Pierre Jacquet (President of the Global Development Network and FARM's Scientific Committee) and Laurent Levard (a specialist in agricultural issues and trade policy at Gret).

The issue dealt with here is of paramount importance for the future of agriculture in Africa: is it in the interests of the sub-Saharan countries of Africa to increase or decrease customs duties on imported agricultural products? Our experts' answers are nuanced, and pragmatism is the byword. Any increase would, in effect, penalise the urban populations by increasing the prices of imported foodstuffs. Any decrease, by bringing down the prices of imported foodstuffs, would penalise smallholders who would thus be subjected to fiercer competition from products bought abroad. The question of the level of customs duties needs to be looked at within the broader framework of the countries' agricultural policies. Indeed, a decrease of taxes on imported goods can only be justified if it goes hand in hand with government investments to improve the productivity and, therefore, the income of small farmers. It is the only way to compensate for the income lost by the latter due to competition from imported products.

Source: FARM - based on harmonised MAcMap-HS6 data from CEPII and the ICC

Source: FARM - based on harmonised MAcMap-HS6 data from CEPII and the ICC

In 2013, all the sub-regions, with the exception of southern Africa, protected their agriculture less from the rest of the world than from the continent's own sub-regions

1- The 'price dilemma in food supply'

2- Trade agreements

Individual African governments have some theoretical room for manoeuvre to increase the duties applied up to the level of the tariffs consolidated at the WTO.

But this room is limited by:

In conclusion